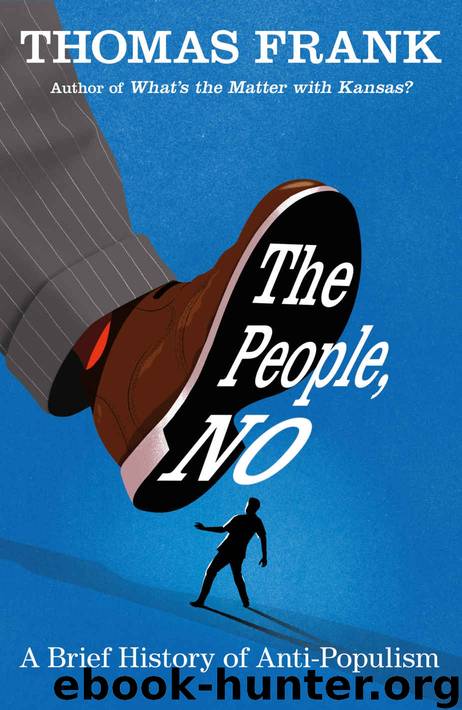

The People, No by Frank Thomas

Author:Frank, Thomas [Frank, Thomas]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.

Published: 2020-07-13T16:00:00+00:00

It was a remarkable speech in many ways, not least because in this passage King got the broad sweep of the Populist story right. By 1965 that word and that story had grown cloudy with demonization of the sort we saw in the last chapter. Indeed, before the decade of the 1960s was out, the media would crown as America’s premier populist none other than King’s nemesis George Wallace, the snarling segregationist who sat in the Alabama governor’s chair at the moment King spoke.

But for now that poisonous irony was still in the future. In 1965 idealism was still capable of carrying the day, and King looked back through the fog of confusion to recall how America’s original movement of working-class unity was defeated. It wasn’t just a historical point of interest for him. By describing Populism’s goal as a “great society”—President Lyndon Johnson’s name for his civil rights and anti-poverty measures—King was suggesting that the movement of the 1890s had an obvious modern counterpart. Working people of both races could come together once more to build a nation of justice and plenty.

What King hinted at, others stated directly. Michael Harrington, the democratic socialist author, was in the audience in Montgomery that day and set down the message for readers of the New York Herald Tribune on March 28, 1965: this movement was not going to stop with civil rights. “King and the others made it clear that they look, not simply to the vote, but to a new coalition of the black and white poor and unemployed and working people,” Harrington wrote. “They seek a new Populism.”

Harrington knew whereof he spoke. By “populism” he meant a transracial movement of the working class that aimed to reform capitalism from the bottom up and distribute its wealth more evenly. Harrington was right to attribute such aspirations to King and his fellow leaders in the civil rights movement. He was also right to understand that a populist sensibility, stirred up by the successful struggle for civil rights, was sweeping over the country, building enthusiasm for “participatory democracy” and popularizing catchphrases such as “Power to the People.”

Consensus intellectuals had proclaimed “the end of ideology” just a few years previously, telling the nation that the big political problems had pretty much been solved. Mass movements were things of the benighted past. Today, the leaders of every group were seated comfortably around the boardroom table, and they got along famously with one another. Rationality and pluralism reigned, with stability and equilibrium for all.

But now the men of consensus were rubbing their eyes behind those heavy horn-rimmed spectacles and gaping at what was transpiring outside the faux gothic windows: there were millions of people in the streets, demanding an end to segregation and then to poverty, war, and sexism. There were students sitting in at lunch counters, cops unleashing dogs on protesters, Klansmen blowing up churches, and racists going mad on TV, dumping acid into the swimming pool rather than see it integrated. There were protesters

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Blood and Oil by Bradley Hope(1558)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1415)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1383)

Daniel Holmes: A Memoir From Malta's Prison: From a cage, on a rock, in a puddle... by Daniel Holmes(1324)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(1311)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1292)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1166)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(1154)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(1142)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1129)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(1125)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(1112)

A Woman by Sibilla Aleramo(1091)

Cleopatra by Alberto Angela(1091)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(1072)

John (Penguin Monarchs) by Nicholas Vincent(1067)

Reading for Life by Philip Davis(1023)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(1022)

The Life of William Faulkner by Carl Rollyson(977)